Neural Architecture Search

Today we are going to dive into an idea that some may fear, and others may praise: AI training itself. Well, in reality the idea is a bit different from an AI training itself, neural architecture search consists of using a network to design other networks in a similar way a human would do it, but automatically. The process can be described as follows.

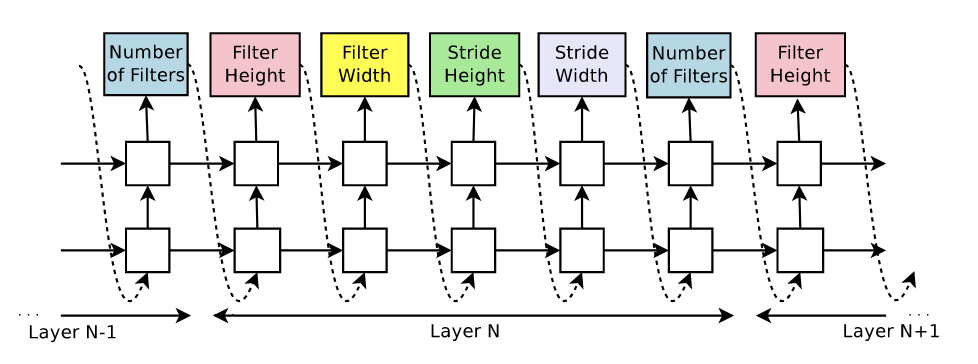

The blue box is the network we want, it can be a Convolutional Neural Network to classify images, or a recurrent neural network to do sentiment analysis. On the other side, the red box is the network that is going to design the solution to our problem for us. However, the controller is not going to output the full code solving your problem, it is not so smart. Instead, it is going to generate the hyperparameters of your network, they can be the filter size, the number of channels of your convolutional layers, or the number of layers of your LSTM, I’ll talk in more details later which hyperparameters can be predicted.

But first, how are we going to train the controller? Because training the supervised model is easy, you throw some data to it and apply gradient descent. However, the controller is not a supervised model. There is no data about the hyperparameters and there is no loss function between the values it gives and the optimal values because, of course, we don’t know the optimal values. Nevertheless, we do have a reward function: the accuracy of the child network. And so we can apply the reinforcement learning paradigm. There is still one problem, the accuracy is a reward function, but it is not differentiable, and we don’t know how it relates to the hyperparameters so it seems that we cannot compute the gradient, and therefore, we can’t apply gradient descent. The currently used solution for that problem was invented by Williams in 1992, they derived the following formula for the gradient:

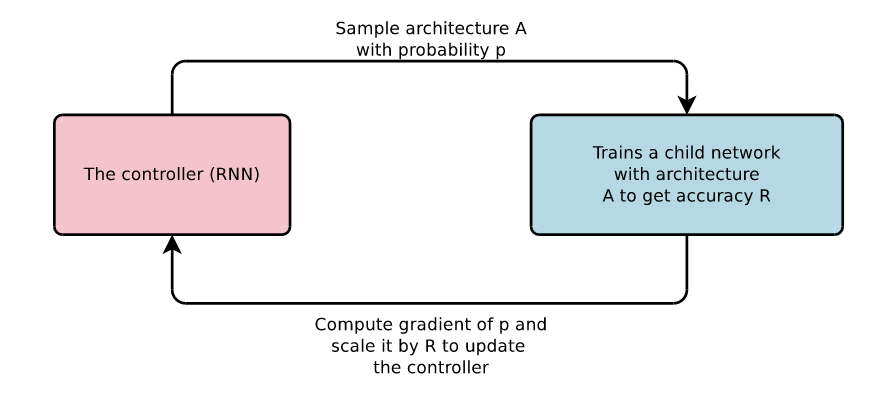

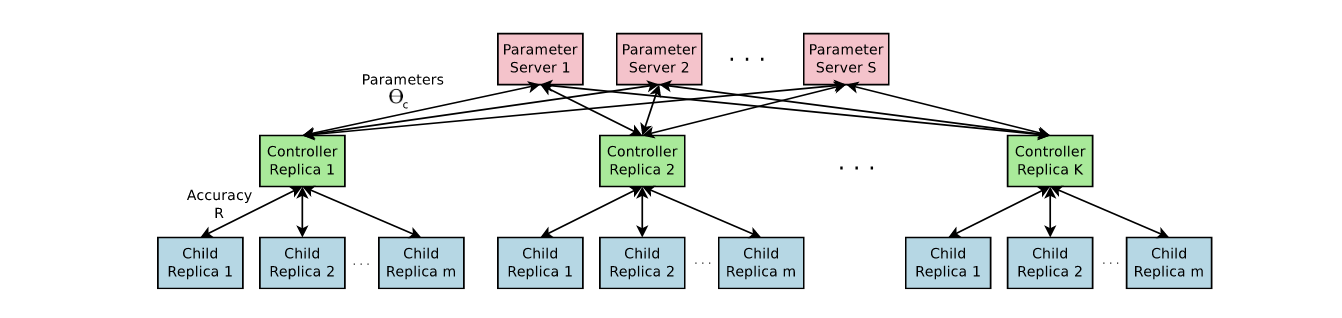

That formula deserves its own post, but for now just bear in mind this is the gradient used to train the controller. The process is fairly simple, withdraw an architecture from the controller, train the architecture in a supervised manner and get a validation accuracy. Use that accuracy as reward and train the controller using the above gradient. Repeat suficiently many times and voilà, your controller has learnt to design architectures. The process is illustrated below. Several controllers are trained in parallel due to the high number of attempts the controller needs in order to achieve good performance. Remember, the controller is learning by try and error.

Now, the details. What is the controller, exactly? In the original paper it was an LSTM, however, any architecture valid for correlated data can be used, like a transformer. But, the NAS article was published the same year as the transformer paper, so they could only try the LSTM because there was no transformer at the time. More precisely, this is the scheme they present in their paper:

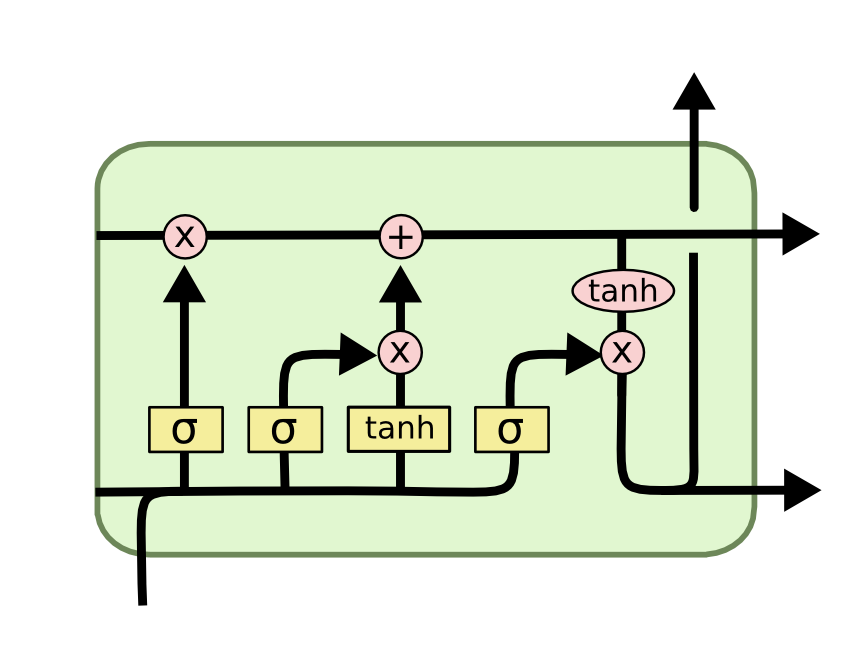

As you can see the controller is predicting very simple parameters, the parameters of a CNN that we normally ignore and use by default. But don’t be fooled by its simplicity, it can get quite complex. Imagine we want to design a recurrent neural network, similar to the LSTM or the GRU. There are hidden states and hidden memory cells but, what are the connections? For the LSTM the connections are the ones shown below.

So think about all those arrows, what if I told you that with neural architecture search we can learn which arrows are the optimal? If you want to know how, wait for the next part in this series.