Modelling a padel match with Hidden Markov Models

Imagine you are at a padel match. You watch the ball go from one side to the other, hit the wall, hit the ground, the net, and after some time someone wins the point. In your head you are following the state of the match until the end to know the winner. Imagine now that you were distracted by a fly and lost concentration on the players. You don’t know what has happened when you were distracted but you managed to watch the last part of the point and so you still know who is the winner. How can we replicate this situation with a model? Which is the correct model to manage situations where you can lose track in the middle but by looking the last part you know the result? The property of only needing to know the last part to know the result is called the Markov property. So a suitable model for this task is a Hidden Markov Model.

In this series I will describe how to properly design a Hidden Markov Model (HMM from now on) to keep track of the state of a padel match. I will also provide functional python code that you could play with. And as extra material I will talk about unit testing and how to use unit tests to incrementally build a model like this one. Let’s begin.

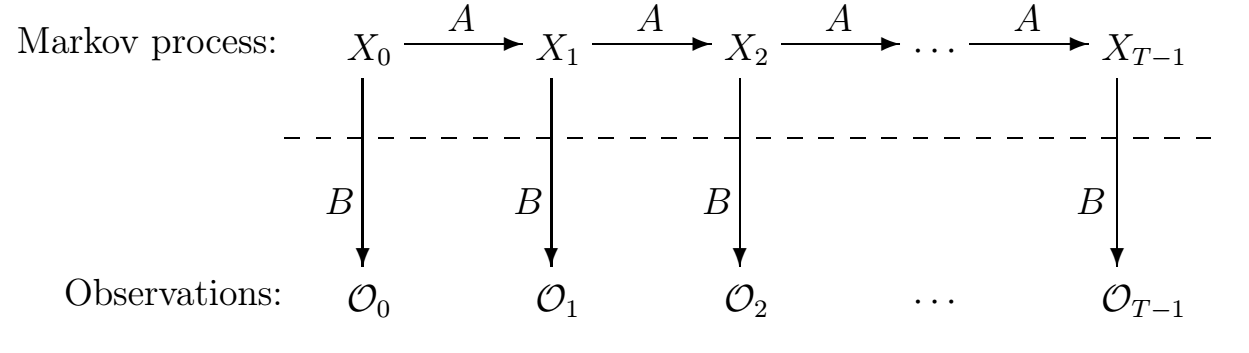

First of all a rapid introduction on HMM and how to code them. A Hidden Markov Model has two main elements: hidden states and observations. The hidden states are what represent the model, in the padel case a hidden state can be first service, or ace or second service. The observations are what you can observe directly, continuing with the analogy an observation can be when the ball hits the ground. What the HMM does is to infer the hidden states based only on a sequence of observations. If you watch that the first player hits the ball and then the ball hits the ground twice on the other side, you can infer that the sequence of states is first service and then ace. A more abstract scheme is shown below.

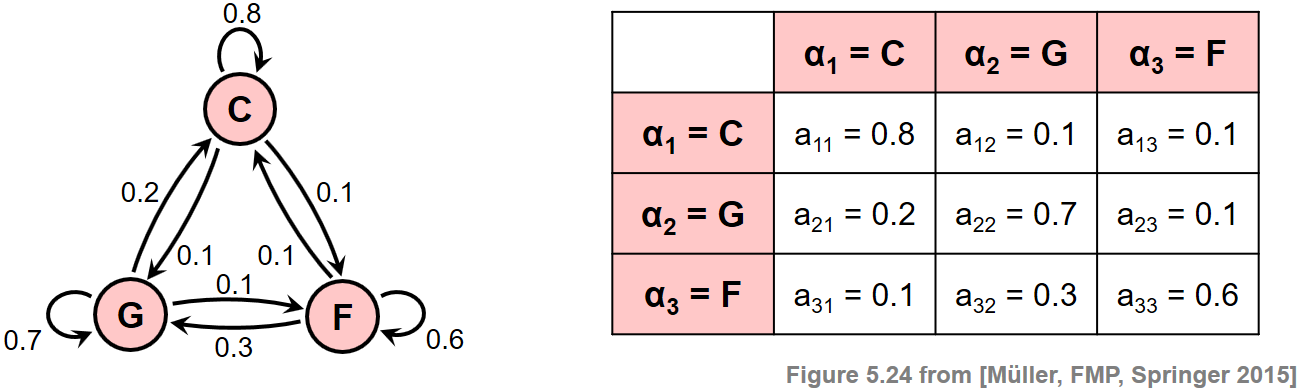

Every arrow represents a transition either between hidden states or between a hidden state or an observation. Each transition is nothing more than a probability. For example, the probability of going from second service to first service is zero because the first service always goes first. The transitions between hidden states and observations are called emissions. One emission could be that the probability of observing the ball hit the ground after first service is $0.5$. The transition and emission probabilities are represented as matrices. Below you can see the transitions of an example from a toy HMM.

Once you have a HMM there are three things you can do with it. Given a sequence of observations you can decode the most probable sequence of hidden states with an algorithm call Viterbi’s. You can estimate the internal probabilities of the HMM using several sequences of observations with the Baum-Welch algorithm. Or you can sample a new sequence of observations. We are only interested in the first one, decoding. The transition and emission probabilities will be designed to model the rules of a padel match.

Now that we have seen the theory, let’s see how we can decode sequences in Python. As you may have guessed there are libraries that implement all the previously mentioned algorithms. My favorite one so far is hmmmkay. It is quite easy to use and is fast enough for my use cases. You can create a HMM with a few lines of code. See below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from hmmkay import HMM

folder_path = 'graphs/'

transition_probas = pd.read_csv(folder_path + 'A.csv', index_col=0)

emission_probas = pd.read_csv(folder_path + 'B.csv', index_col=0)

hidden_states = emission_probas.shape[0]

init_probas = np.zeros(hidden_states)

init_probas[0] = 1

hmm = HMM(init_probas, transition_probas, emission_probas)

The important method is HMM(init_probas, transition_probas, emission_probas). Given the transition and emission matrices and given also some initial probabilities for the hidden states it returns an object that can decode any sequence. The details of how to create the matrices will be described in later posts of the series. I can advance you a bit about the process. You first begin by drawing a graph in paper with the transitions you like, you then parse that graph in paper into a graph in digital format (.gml). And finally, you use the adjacency matrices of the graph as the probability matrices. But for now, let’s assume we already have those files. How can we decode a sequence? Like this.

1

decoded_seq = hmm.decode(sequences)

The only concern to bear in mind is that the input and the output are numbers starting from zero. You need to parse those values to have something significant. I normally use the column names of the matrices as dictionaries to parse the sequences.

1

2

3

4

5

6

indexer_hidden = dict()

for k, col in enumerate(transition_probas.columns):

indexer_hidden[col] = k

indexer_obs = dict()

for k, col in enumerate(emission_probas.columns):

indexer_obs[col] = k

Putting everything together, to decode a sequence the program would look something like this code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

### ace in first service ###

sequence = ['player-hit', *['flying'] * 10, 'bounce-ground-receiver', *['flying'] * 10,

'bounce-ground-receiver', *['flying'] * 10, 'end']

sequences = [[indexer_obs[obs] for obs in sequence]]

decoded_seq = hmm.decode(sequences)

decoded_seq = [hidden_states[idx] for idx in decoded_seq[0]]

print(decoded_seq)

# Result: ['1st-serve', 'flying-1st-serve-0', 'flying-1st-serve-1', 'flying-1st-serve-2', 'flying-1st-serve-3',

# 'flying-1st-serve-4', 'flying-1st-serve-5', 'flying-1st-serve-5', 'flying-1st-serve-5', 'flying-1st-serve-5',

# 'flying-1st-serve-5', 'in1', 'flying-in1-0', 'flying-in1-1', 'flying-in1-2', 'flying-in1-3', 'flying-in1-4',

# 'flying-in1-5', 'flying-in1-5', 'flying-in1-5', 'flying-in1-5', 'flying-in1-5', 'ground', 'flying-ground-0',

# 'flying-ground-1', 'flying-ground-2', 'flying-ground-3', 'flying-ground-4', 'flying-ground-5',

# 'flying-ground-5', 'flying-ground-5', 'flying-ground-5', 'flying-ground-5', 'Point-server']

Don’t worry if you don’t understand all this fuzzy names, they are the names that I chose for the hidden states and observations. On my next post I will explain in detail what everything means. For now I just want you to notice that the HMM is correctly identifying the winner in this point. The sequence of observations correspond to an ace in the first service. The player hits the balls and it bounces twice in the other side. Any person watching the match will automatically identify that as an ace. Here, it gives more information than that. It recognizes the instant in which the ace is achieved. The hidden state in1 means the ball has correctly entered into the other side and the state ground means that it has bounced again in the ground. After a while of having the ball flying, the model outputs the state Point-server correctly giving the victory to the server.

On my next post I will talk about the process of designing the transition and emission matrices. I will also talk about what is reasonable to be defined as observation and which hidden states are needed. And on a later post I will cover a lesson on noisy decoding. One important feature of Hidden Markov Models is that they can decode the sequence of observations even if it is wrong at some point. Like I said at the beginning you could ignore the match for some time and then you would still be able to recognize the winner. HMMs can go even further. Imagine that you are not looking the match and you are just hearing it from the radio. If the commentator makes some mistake you may hear something impossible like a player hitting twice the ball without the match finishing. HMM can decode the sequence correctly even in those situations. That is because HMMs work with probabilities. If a player hits twice the ball and the game continues, the HMM will identify that second hit as a mistake and ignore it. Of course, if the sequence is completely wrong, the result will be wrong too. But HMM are quite robust to noise in the input if you design them carefully. See you on my next post to learn how to design Hidden Markov Models.